Karachi is hard to love. Its treacherous seas tried to devour Sanval, the husband of the city’s founding matriarch, Kolachi. Its lush mangroves lured the city’s first colonising fleet, only to disappoint as a “gloomy portal of a desolate and uninteresting country”. Lady Lloyd felt so sick during her stay that she had her husband make a pier in Clifton that would take her, every evening, as far away from the city as possible. TE Lawrence, of the Lawrence of Arabia fame, was so unimpressed by the “sorry place” that he barely ever left his garrison at Drigh Road in a year and half of being posted here. Fehmida Riaz wistfully longed for a liver firm enough to bear the city. Perveen Shakir swore that it was “a whore”.

But Karachi is also hard to ignore. Shah Abdul Latif bemoaned the city’s metaphorical whirlpools. “Whoever goes to Kalachi, never comes back,” he lamented. Legions of peripatetic saints, from the 7th to the 20th century, made this unremarkable pitstop their home. One Pir, Mangho, and at least seven Shahs — Abdullah, Ghaiban, Hassan, Yousuf, Misri, Ali and Mewa — retired along the sea and riverfront, like true city elites. Millions have followed in their footsteps since, including my family, in waves after waves. Today, anywhere between 15 to 20 million people, depending on who you ask, live here precariously, suspended between the city’s promise and peril.

This essay, and the accompanying set of maps, are not a descriptive history of Karachi’s public transit or a prescriptive proposal for its future. This is a story — of a colonial hangover, a race to the bottom, a fever dream and a future set right. It is a manifesto for a more accessible and equitable city. It is an invitation for a conversation on why we, the residents of Karachi, deserve better. If nothing else, it is a reverie for a city that is not impossible to love.

Prologue

Cities are abstractions — ideological, material, and social. For all their shrines and temples and claims to divine origins, they are essentially human: sites for flows of people, their ideas, and goods. The more easily people, goods and ideas can flow through, and within, a city, the more successful they become. No one moves to a stagnant or decaying town, no matter how beautiful the landscape. Karachi’s prosperity and promise made it the destination of choice for migrants not just from the length and breadth of Pakistan, but from Iran and Afghanistan to Sri Lanka and Bangladesh throughout the latter half of the 20th century.

After the shock of partition, where the population swelled from 400,000 in 1941 to a million in 1950, Karachi galloped at an average growth rate of around five per cent for the next 50 years. At the turn of the century, in the year 2000, the city clocked in roughly 10m residents. In this half century, Karachi was to south and west Asia what New York was to a war-torn Europe in the first half of the 20th century. From 1890 to 1945, the newly consolidated New York City grew from a regional powerhouse of 1.5m residents to a 7.5m strong global metropolis. Despite this similarity in population growth, their trajectories could not have been more different. New York harnessed this half century of migration to become a global financial capital. Karachi squandered this opportunity and ended up being an inglorious regional backwater.

In 1948, the two cities briefly collided in a fortuitous and almost foretelling encounter. Ghulam Ali Allana, the first mayor of independent Karachi, visited New York during a larger official visit that he documented in a travelogue. Like a fish out of water, he was unable to grasp the complexity of post-war, diverse, eclectic New York. With all the energy of a middle-aged, privileged Pakistani man, he was most impressed by Times Square and the synchronised traffic lights, and hoped to bring the latter to Karachi. The city’s lifeline and engineering marvel, the subway, merely got a passing mention. A more perceptive administrator would have picked up on the transformative power of rapid mobility, but alas, not Allana. He took taxis everywhere, and frequently tripped over his racist, classist and moralistic ideals, as he uncritically navigated New York’s youthful post-war exuberance. By the time his trip ended, it was painfully obvious that Karachi and New York exist in two wildly divergent worlds and will continue to in the foreseeable future.

Colonial hangover

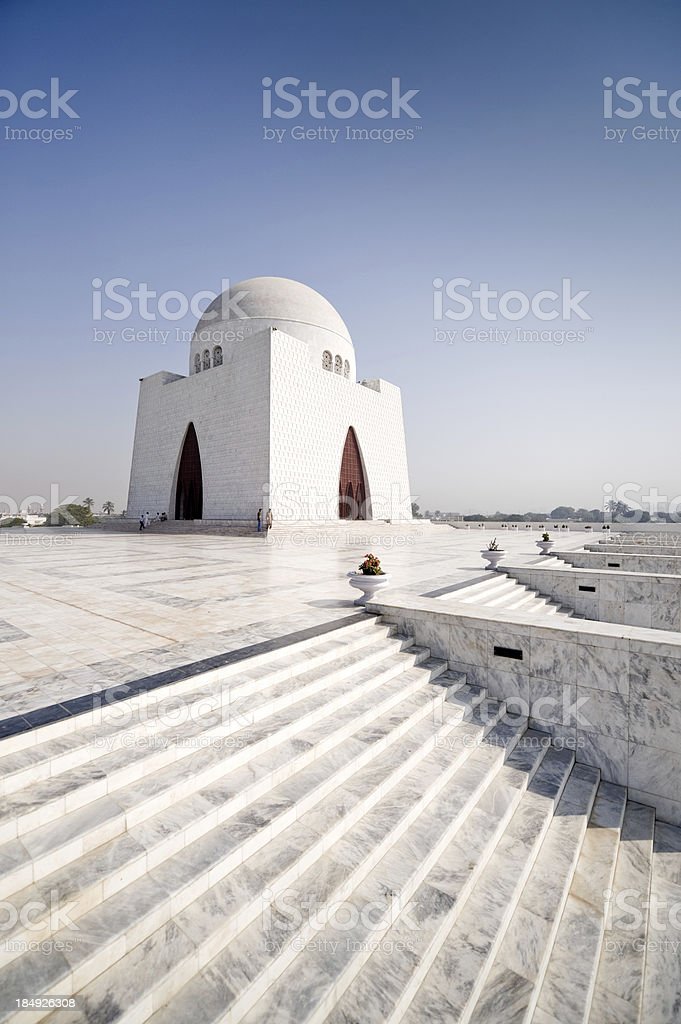

When the first post-partition migrants arrived in the early 1950s, Karachi was the city worth moving to. The city had a centuries-long maritime tradition, cemented by the thriving seaport, an airport and rail connections to up-country. There were robust municipal services, public transport, and an air of cosmopolitanism. A 1930 colonial town planning consultant’s report termed Karachi “one of the cleanest and best kept cities … in India”.

The shock of partition was still raw, and the bulk of the city’s non-Muslim population had left. Their markers, however, were aplenty. Standing at Eidgah on Bandar Road and looking south through the dust-specked late afternoon light, the domes and spires of municipal buildings, commercial offices, clock towers and public halls, the shikhara of the Swaminarayan Temple and the tapered minarets of New Memon Masjid must have been both a spectre and a spectacle. It left an indelible mark on at least one immigrant from Hyderabad Deccan, Ahmed Rushdi, whose preppy song “Bandar Road se Keamari” would immortalise the road and jumpstart Rushdi’s career as a playback singer.

While Rushdie set out in his horse-drawn carriage, Bandar Road bustled as the spine of the country’s only urban transit system. Sixty-four petrol-powered trams shuttled citizens from Cantt and Soldier Bazar to Saddar, and down Bandar Road all the way to Keamari, all for an anna. A branch line from Gandhi Garden along Lawrence Road brought residents of the old, dense quarters — Bhimpura, Chakiwara, Ramswamy, Ranchore Lines — all the way down to the boisterous Boulton Market junction. In 1949, the East India Tramway Company was sold to a Karachi merchant, Sheikh Mohamedali, and became the Mohamedali Tramways Company.

Karachi in the 1950s was a dense, multi-ethnic, multi-class city, and both my sets of grandparents set roots in close proximity to Bandar Road and Cantt Station. It was a worthy capital of this new country and the energy was palpable. The city was bursting at its colonial seams, and foreign consultants had been summoned to develop a Greater Karachi Plan to accommodate the influx of migrants and the demands of a new capital. A 1952 masterplan plan by a consortium of British and Swedish firms, Merz Rendel Vatten (Pakistan) (MRVP), expected Karachi to treble in population to 3m by the year 2000. The Report on Greater Karachi Plan consolidated the primacy of Bandar Road and extended the administrative centre of the capital further north-east along the same axis. For future growth, it proposed dense, self-sustaining satellite spurts, in all four directions, all connected by a robust light rail public transport system and supplemented by rapid and local buses. In comparison, mass transit did not feature in any of Lahore’s masterplans until the 1990s.

The exuberance, however, was short-lived. The capital was shifted to the north, and the rug was pulled from under the aspirations of the 1952 MRVP plan. Instead, irked by the presence of refugees in the city centre, the martial law administration commissioned a Greater Karachi Resettlement Plan in 1956, this time by a Greek firm Doxiadis Associates (DA). The firm proposed two satellite townships, Landhi-Korangi in the east and New Karachi in the north. Dictator Ayub Khan, desperate for visible signs of progress, ran with the idea of Korangi before DA could even finish the detailed plans, and built 15,000 houses by 1959. But once the dust settled, there was little of the promised industry to support the residents and the Korangi dream started falling apart as quickly as it had been conjured into being.

Before the lights went out though, Karachi experienced a flash of public work brilliance the likes of which it will not see for decades. The city built the country’s first urban rail transit system, the Karachi Circular Railway (KCR), a scaled-down version of the local railway system proposed in the MRVP Plan of 1952. It was initially launched for goods and limited internal service in 1964 but, when the loop was completed in 1969 and service was opened to the public, it was an instant hit. Ridership soared almost immediately. At its peak, over a hundred trains would shuttle people constantly across the loop and main line of the KCR.

It was an urban marvel, both in its essence (rapid mobility for everyone) and ambition (a well-connected, growing city), but unfortunately it arrived at the wrong place, at the wrong time. Globally, the private automobile was ascendant and cities were rapidly reconfiguring themselves to accommodate this new beast. Under Robert Moses, New York had been shaped in the image of the automobile — highways running down the east and west coast of Manhattan, connected to bridges strung over the East River to Brooklyn, Queens and the Bronx. The impact was not limited to private transport only. After a 30-year building spree, subway construction in New York City came to a halt and the dense network of electrified streetcar lines connecting Brooklyn to Queens was replaced by a fleet of buses. Rail-based public transport will take a back seat for some time now.